Archaeological Investigations of a Probable Slave Quarter at Rich Neck Plantation

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 0395

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

2009

Archaeological Investigations of a Probable Slave Quarter at Rich Neck Plantation

Principal Investigator

Marley R. Brown III

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Department of Archaeological Research

1991

Re-issued

November 2002

| Page | |

| List of Figures | ii |

| List of Tables | ii |

| Acknowledgements | iii |

| Introduction | 1 |

| Property History | 3 |

| 17th Century | 3 |

| Ludwell Tenure | 3 |

| Previous Archaeological Research | 8 |

| Archaeological Methods | 9 |

| Archaeological Results | 9 |

| Plowzone | 11 |

| Root Cellar A | 11 |

| Root Cellar B | 11 |

| Root Cellar C | 11 |

| Discussion | 11 |

| Structural Remains | 14 |

| Artifacts from Root Cellars | 14 |

| Comparative Analysis | 17 |

| Conclusion and Recommendations | 21 |

| Bibliography | 25 |

| Appendices | |

| Artifact Inventory | 28 |

| Ceramic and Glass Vessels | 32 |

| Page | |

| Figure 1. Project Area | 2 |

| Figure 2. Desandrouins Map | 4 |

| Figure 3. Rochambeau Map | 6 |

| Figure 4. Plan of Archaeological Features | 9 |

| Figure 5. Root Cellar A, Plan and Profile | 12 |

| Figure 6. Root Cellar B, Plan and Profile | 13 |

| Figure 7. Root Cellar C, Plan and Profile | 13 |

| Figure 8. Post in the Ground Architecture | 15 |

| Figure 9. Root Cellar Artifacts, Yorkshire 44Wb52 | 18 |

| Figure 10. Root Cellar Artifacts, Root Cellars A & B | 21 |

| Figure 11. Root Cellar Artifacts, Comparison of Yorkshire & Carter's Grove | 22 |

| Page | |

| Table 1. Ceramics and Glass from Root Cellar B | 19 |

| Table 2. Ceramics and Glass from Root Cellar A | 19 |

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are in order to a number of people who helped make this project possible. Chuck and Janice Nimmo, owners of 129 Yorkshire Drive, are to be commended for recognizing the importance of what their yard contained and for calling it to our attention. Greg Brown, Andrew Edwards and Nate Smith of the Department of Archaeological Research gave freely of their time to excavate the site. Amy Kowalski, also of the Department of Archaeological Research, coordinated the lab work, and Kim Wagner provided the report graphics. Greg Brown also very graciously edited this report. Several students enrolled in the William and Mary/Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Archaeological Field School, including Melanie Perreault, Matt Laird and Amy Vinroot, also served as crew members. Doug Lockwood, of Ground Effects Landscaping, graciously removed the soil overburden from the site for us in order to speed our work. Thanks are also in order to Ivor Noël Hume, who originally examined the site and called our office.

Introduction

In early August 1990, the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's Department of Archaeological Research conducted salvage archaeology on the property of Chuck and Janice Nimmo, at 129 Yorkshire Drive in Williamsburg, Virginia (Figure 1). During landscaping of their yard, the Nimmos discovered in-situ brick and a dark soil stain, as well as numerous fragments of ceramics and wine bottle glass dating to the colonial period. Consultation with Ivor Noël Hume, retired archaeologist for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, resulted in a three-day salvage of the site by the Department of Archaeological Research.

Using Department of Archaeological Research staff, as well as students enrolled in the College of William and Mary/Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Archaeological Field School, a total of three features were excavated and recorded. With the assistance of Doug Lockwood of Ground Effects Landscaping, the topsoil and plowzone covering the site were stripped away, leaving only sterile subsoil clay with features cutting through it. The features which were discovered have been interpreted as root cellars, remnants of a structure shown on the 1781 Desandrouins Map and part of the Ludwell Rich Neck Plantation.

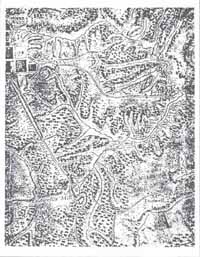

2Property History1

Documentary research indicates that this property comprised part of the Rich Neck plantation, owned from the 17th through the 19th centuries by the Ludwell family of Greenspring. This area is marked on the Desandrouins Map as "M. Ludwell"; the map shows six buildings associated with the plantation (Figure 2). On the map, a road leads from the present-day Jamestown Road to the main group of structures, shown on a ridge overlooking a tributary of College Creek. To the northeast, across Jamestown Road, was Ludwell's Mill, also owned by the Ludwell family. Using the Desandrouins Map as evidence, it is believed that the site salvaged at 129 Yorkshire Drive was that of a support building or dependency connected with the Ludwell Plantation. A building is depicted at this location along the edge of the ravine on the south side of the property.

17th Century

The Rich Neck parcel appears to be a portion of 1200 acres granted in 1635 to George Minifie (or Menifie) Esqr., described as "a neck of land comonly [sic] called the Rich Neck, bounded on w. with a br. of Archers Hope Cr…" (Nugent 1979:24). The precise boundaries of the Rich Neck parcel are unclear, but appear to have extended to the north of Route 5 (Brown and Hunter 1987:81). Menifie, in addition to being a lawyer and a merchant of the Corporation of James City, also served as an agent for the Virginia estates of persons residing in England (Meyer and Dorman 1987:448). After Menefie's death in 1644, the land passed to Richard Kempe, who lived there and was later buried on the property (Goodwin 1971).

Sometime after his 1650 arrival in the colonies and before his death between 1653 and 1656, Sir Thomas Lunsford married the widow of Richard Kempe, who had previously owned the Rich Neck parcel. With Elizabeth Kempe, Thomas Lunsford had one daughter, Catherine (Merz 1976).

Ludwell Tenure

Thomas Ludwell was born in England in 1628. After his arrival in Virginia, sometime before 1660, he patented 500 acres in James City County (Anonymous 1911:209), but it is not clear when or how Ludwell came into the Rich Neck property. He was appointed Secretary of the State of Virginia in 1660, a duty which entailed making reports concerning the condition of Virginia affairs to the English secretary of state. Ludwell died in October 1678 and was buried on the Rich Neck estate (Anonymous 1911:209).

Philip Ludwell I, brother of Thomas Ludwell, was born in England in 1638. He came to Virginia from England around 1660. He served as the secretary of the Colony for Thomas Ludwell between 1675 and 1677, when his brother was in England. Philip probably

4

Figure 2. Desandrouins map.

5

resided at Rich Neck plantation, since he was described in 1680 as Philip Ludwell of Rich Neck. Greenspring Plantation, perhaps the most famous of the Ludwell properties, came into the hands of the family in 1680, when Philip I married the widow of the late Governor William Berkeley of Greenspring (Carson 1954).

Figure 2. Desandrouins map.

5

resided at Rich Neck plantation, since he was described in 1680 as Philip Ludwell of Rich Neck. Greenspring Plantation, perhaps the most famous of the Ludwell properties, came into the hands of the family in 1680, when Philip I married the widow of the late Governor William Berkeley of Greenspring (Carson 1954).

Philip Ludwell became a member of the Virginia Council in 1675, and was later elected Governor of the Province of North Carolina. His son, Philip Ludwdell II, was born in 1672, and later became very active in the colony's politics. He was elected Speaker of the House in 1695, became a member of the Council of Virginia, and was appointed Auditor of Virginia in 1711. When his father returned to England in 1700, he took over the management of Greenspring Plantation, which he later inherited from his father's estate. From his unmarried uncle, Thomas Ludwell, he inherited the plantation known as Rich Neck. During his lifetime, Philip Ludwell II expanded the family property holdings by purchasing land within the town of Williamsburg.

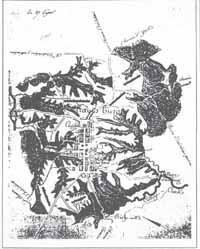

Philip Ludwell III was born to Philip Ludwell II and his wife on December 18, 1716 (Ludwell 1913). After his father's death in 1726/27, Philip Ludwell II owned the Rich Neck plantation, as well as Greenspring Plantation and other nearby properties. Philip III was appointed a member of the Council in 1751 (Virginia Gazette 1751), but returned to live in England after his wife's death in 1761 (Shurtleff 1935). He died there in 1767. His property in Virginia, however, remained known as "Ludwell," as it was shown on the Desandrouins Map from the Revolutionary War era. This map also shows, to the northeast, "Ludwell's Mill," on what is now Lake Matoaka. It is not known when this mill came into existence, although advertisements in the Virginia Gazette mention it as early as 1755. Another Revolutionary War period map (Rochambeau 1781) shows the Ludwell property and mill area marked as "Rich Mill's" (Figure 3).

Philip Ludwell III, at his death, owned numerous large estates which were listed in his inventory, including those at Hot Water, Green Spring, and Rich Neck on the north side of the James River. His Scotland estate was located on the south side of the James River, in Surry County. Upon his death in 1767, the Rich Neck property passed to his youngest daughter Frances. At Frances' premature death, Lucy Ludwell Paradise received the Rich Neck land. A 1767 inventory of Philip Ludwell's estate listed 21 slaves and numerous livestock at the Rich Neck plantation, as well as over 1600 pounds of tobacco and agricultural implements. The Mill Quarter, presumably that associated with the Rich Neck Plantation and Ludwell's Mill, contained eight additional slaves (Ludwell 1913). A letter from William Lee (who married Philip III's daughter Hannah Philipa) to Robert Carter Nicholas, dated September 11, 1770, states that "Mr. Paradise's people" were going to be moved to the quarter at Rich Neck Mill (Southall Papers).

The Rich Neck tract which Lucy Ludwell Paradise and her husband owned consisted of 3459 acres in 1796. Lucy and John Paradise lived in London, with the property being managed by Cary Wilkinson. By 1809, 800 acres of this property had been sold, with the remainder of the property remaining within the Ludwell-Paradise family for some twenty four years following Lucy's death in 1814. In 1838, the remaining acres of the former Rich Neck plantation were sold, including the mill on what is now Lake Matoaka. The mill portion of the property was purchased by William Jones. Numerous transactions for various

6

Figure 3. Rochambeau map.

7

parts of this property were conducted during the remainder of the 19th century. The area is shown on the Gilmer Map of 1863 as "Jones Mill (destroyed)." Numerous transactions for various parts of this property wore conducted during the remainder of the 19th century.

Figure 3. Rochambeau map.

7

parts of this property were conducted during the remainder of the 19th century. The area is shown on the Gilmer Map of 1863 as "Jones Mill (destroyed)." Numerous transactions for various parts of this property wore conducted during the remainder of the 19th century.

Numerous property owners, including the Geddy family of Williamsburg, Walsingham Academy, and the residents of Yorkshire development, own a large portion of the property which encompasses the 17th- and 18th-century Rich Neck plantation.

Previous Archaeological Research

In the spring of 1988, the Tidewater Cultural Resource Center of the College of William and Mary performed a Phase I survey of the proposed 45-lot Yorkshire of Williamsburg residential development. This work was initiated as a result of local residents finding and reporting colonial-period artifact scatters in the new road cuts for the development. Since the area slated for development corresponded with that shown through map and other documentary evidence to be that of the 17th- and 18th-century Ludwell Rich Neck plantation, an archaeological testing program was effected.

As a result of this survey, three sites were discovered and recorded with the Virginia Department of Historic Resources. These included the site of the Ludwell's Rich Neck Plantation (44Wb52), a late 19th/early 20th-century tenant farm house (44Wb53), and the location of an earthen dam and ice pond (44Wb54). The findings of his survey are detailed in Archaeological Survey of the Rich Neck Plantation (Samford and Brown 1988), on file at the Virginia Department of Historic Resources in Richmond and at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's Department of Archaeological Research.

Archaeological Methods

The 1988 archaeological testing had shown that the area of the plantation site (44Wb52) had been plowed, probably in the 19th and early 20th centuries. According to local resident Fred Frechette, the area had also been extensively logged during the 1950s. As a result of these activities, the soil had been disturbed to a depth of approximately a foot over the entire area under examination in 1990. In order to speed excavation, a backhoe was brought in to strip the overburden of soil from the site. As a result of stripping most of the front yard of 129 Yorkshire Drive, three archaeological features were uncovered (Figure 4). Several test holes were also excavated along the wooded eastern edge of the Nimmo property to determine, as much as possible, spatial limits of the salvaged portion of the site.

Figure 4. Plan of archaeological features.

Figure 4. Plan of archaeological features.

After being mapped in plan, the three features were excavated using trowels. The soil from the features was screened through ¼-inch hardware cloth, and soil samples were saved for future seed and pollen analysis. Record keeping procedures for the site were consistent with those used by Colonial Williamsburg's Department of Archaeological Research.

Artifacts recovered from the site were taken to the Department of Archaeological Research for processing. After being washed, inventoried and mended, the artifacts were returned to Chuck and Janice Nimmo for curation.

Archaeological Results

A total of three features and one soil layer were discovered on the property. Each of these features, interpreted as root cellars, are described below.

Plowzone (44Wb52-1)

The plowzone layer (approximately 1.0' thick), which covered the entire site consisted of a medium grey sandy loam with charcoal and brick flecking. Numerous artifacts (see Appendix 1) were recovered from the plowzone. Although the majority of the artifacts dated to the 18th century, some modern material, such as solarized glass, cement, and bathroom tiles, probably were debris from the early 20th-century tenant farmer living to the northwest and the more recent house construction on the lot.

Root Cellar A

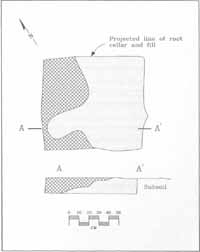

Root Cellar A (44WB52-2) had been cut and partially destroyed by the backhoe during yard landscaping. After scraping away the surrounding soil with trowels to locate edges, it appeared that the feature consisted of a rectangular hole (3' NS × > 3'3" EW) which had been cut into the surrounding yellow clay subsoil (Figure 5). The soil filling the feature was a mixture of dark grey sandy loam mixed with yellow clay. Charcoal, brick fragments, and numerous artifacts were contained with the fill of the root cellar. Fifty-four percent of the recovered ceramics and glass artifacts showed evidence of burning.

Root Cellar B

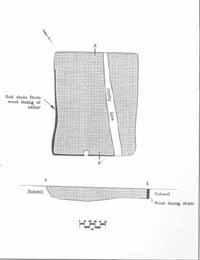

The second root cellar (44Wb52-6) was, like the first, excavated into the yellow clay subsoil. Measuring 5' 1" x' 6' 2", it was rectangular in shape, and had been recently cut by a telephone or some other small utility line (Figure 6). The soil contained within the feature was a dark grey sandy loam, with heavy concentrations of charcoal, burned brick fragments and red wood ash. Narrow soil stains and concentrations of nails along the south and west edges of the feature indicated that the root cellar had been lined with wooden boards measuring 1 1¼" thick. Evidence of this wood lining appeared only on the south and west sides of the feature. As with Root Cellar A, most of the top of the root cellar had been destroyed by plowing, with only the bottom 10" of the feature remaining intact. The feature fill, like that of Cellar A, contained domestic artifacts, also dating mainly to the late 18th century.

Root Cellar C

The third root cellar (44Wb52-3) differed from the others in that its bottom had been paved with bricks (Figure 7). The bricks, salmon and orange in color and laid in a running pattern, had not been mortared together. This feature, measuring 4'3" × 3'11", had been partially uncovered by the backhoe during the initial yard landscaping. As a consequence, several of the bricks had been displaced from the feature's southeast corner. The remaining

12

Figure 5. Root Cellar A, plan and profile.

bricks were uncovered by troweling and shoveling away the plowzone covering them. No fill layer remained in association with this feature. These bricks have also been interpreted as the remains of a root cellar for two reasons. First, it was apparent that the bricks had been laid into the bottom of a hole which had been cut into the yellow clay subsoil. Also, the brick were found at the same horizontal level as the bottom of the other two root cellars, indicating that the level of the bricks would have been below surface grade during the late 18th century, ruling out its use as a paved work area. Although it is possible that the brick represent the remains of a hearth base, this is not likely, since the brick paving was not mortared. Additionally, there was not enough brick debris found over the remainder of the site to indicate that the building contained a brick hearth. No intact fill was found overlying the brick paving, and there were no artifacts found in association with this feature.

Figure 5. Root Cellar A, plan and profile.

bricks were uncovered by troweling and shoveling away the plowzone covering them. No fill layer remained in association with this feature. These bricks have also been interpreted as the remains of a root cellar for two reasons. First, it was apparent that the bricks had been laid into the bottom of a hole which had been cut into the yellow clay subsoil. Also, the brick were found at the same horizontal level as the bottom of the other two root cellars, indicating that the level of the bricks would have been below surface grade during the late 18th century, ruling out its use as a paved work area. Although it is possible that the brick represent the remains of a hearth base, this is not likely, since the brick paving was not mortared. Additionally, there was not enough brick debris found over the remainder of the site to indicate that the building contained a brick hearth. No intact fill was found overlying the brick paving, and there were no artifacts found in association with this feature.

Discussion

As became rapidly evident as digging progressed, activities occurring in the 19th and 20th centuries had severely damaged the Yorkshire site and destroyed much of the information which could have been used to more accurately assess what had happened there. The features located during the excavation, however, are suggestive of archaeological remains generally found in association with Chesapeake slave houses in the 18th century. This interpretation fits well with the historical documentation for the property and it is concluded that this was the former location of a late 18th-century slave dwelling on the Ludwell Rich Neck Plantation. This conclusion will be supported by the following discussion of both the artifacts and the structural evidence.

Structural Remains

During the excavation, none of the types of archaeology associated with colonial-period buildings (brick foundations, hearth bases, structural post stains) were revealed. In fact, the only structural remains took the form of three root cellars which were found paralleling the natural ridge. Do these cellars alone constitute enough evidence that a structure actually stood at this location?

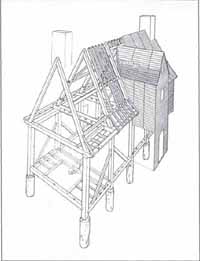

To answer this question, one needs to examine the architecture of the Virginia colonial period and the archaeological remains that they leave behind once the buildings have been destroyed. Buildings constructed with continuous brick or stone foundations leave the most substantial archaeological remains, in the form of the below-ground portions of the brick or stone wall lines even if the brick or stone have been savaged after the building was destroyed, a rubble and mortar-filled trench would be evident, indicating where the foundation had been seated. A less permanent form of construction, known as post-in-the-ground or earthfast, leaves less tangible traces (Figure 8). These buildings contained "framing members… standing or lying directly on the ground or erected in postholes" (Carson et al. 1981: 136) . Since this was a less expensive form of construction, it was often used in the 18th century for outbuildings, such as stables, sheds, and slave housing. Archaeologically, these buildings leave soil stains indicating where structural posts had been buried upright. In addition to leaving a footprint of the building's dimensions, these postholes also help date the lifespan of the building. Artifacts recovered from the soil within the hole dug to seat the wooden post aid in dating when the building was constructed. Those recovered from the soil where the wooden post rotted in place or was pulled from the ground help determine when the structure was destroyed.

Based on evidence from numerous colonial period sites in Virginia, Maryland, and elsewhere, it was not unusual for slave houses to have been built using post-in-the-ground construction, or the even less permanent method of placing the structure on a wooden sill resting directly on the ground surface. This inexpensive, impermanent construction is the reason that so few slave houses, barns, or sheds constructed in the 18th century survive today. Either of these methods of construction left the building very susceptible to decay through contact with the ground surface or damage by insects.

15 Figure 8. Post in the ground architecture.

Figure 8. Post in the ground architecture.

At the Yorkshire Drive site, the top twelve inches of soil had been disturbed by later plowing and to a lesser extent by logging activities. The resulting damage to an archaeological site from plowing depends on the character of the building remains and other subsurface features. A shallow brick foundation wall would be completely destroyed and the bricks scattered around the plowed field. A post-in-the-ground structure will survive somewhat more intact, since the holes dug to seat the support posts are usually deeper than the twelve to eighteen inches affected by the plow. These structures would appear as patterns of posthole stains, leaving information on the size and location of the structure. Since ground sill-laid buildings seldom leave more than a shallow soil stain indicating where the wooden sill rotted in place, all traces of these structures would be destroyed by plowing.

Since no traces of post stains were found intact on the Yorkshire property, this would suggest that the building had either been set on a shallow brick foundation or that it had been a ground sill structure. Given the scarcity of brick fragments seen scattered in the plowzone during excavation, it is most likely that this structure had been placed on a wooden sill. Because of this plowing, no evidence remained to suggest the dimensions of the building, or the placement of other features, such as doorways or chimneys. Chimneys or hearth remains also rarely survive the action of the plow. Recent work at St. Mary's 16 City in Maryland has shown that activity areas outside of structures can be pinpointed by recovering artifacts from the plowzone in a controlled fashion (King and Miller 1987), perhaps suggesting locations of doors and windows. Unfortunately, time and cost limitations precluded this type of recovery at the Yorkshire site. Many of the chimneys built on slave houses appeared to have been constructed of sticks and mud, and supported by sticks. Late 19th-century photographs show the precarious angle of these chimneys and supporting sticks propped against them as a safety measure. If the chimney caught on fire, it was a simple matter to kick away the stick, push the chimney away from the building, and thereby prevent the entire house from catching fire. At Monticello, archaeologists were able to determine former chimney locations on Jefferson's slave quarters through locating concentrations of burned mud and nails representing where such chimney falls had occurred (Kelso 1986:32). Several of these stick and mud chimneys have been reconstructed at the Carter's Grove slave quarters and early 20th-century photographs show that such stick and mud chimneys continued in use into the recent past. Chimneys of this sort leave little more than scorched clay, ashes, and the nails used to hold the wooden logs together, all traces easily obliterated by the plow.

One feature, however, which seems to be found regularly on 18th-century slave house sites in the Chesapeake are root cellars, or underground storage pits, located within the structures themselves (Kelso 1984). Consisting of rectangular holes of varying sizes which have been dug out of the ground and into the underlying clay, root cellars probably functioned in several capacities. Documentation suggests that they were used primarily for the storage of root vegetables such as potatoes, carrots, or turnips. Many of the excavated examples have been located in front of fireplaces within the households, since the heat from the hearth would have kept the vegetables from freezing in the winter. Additionally, archaeologists have found that these pits served as storage areas for other household items as well. Tools such as hoes, trowels, and cutlery have been found on the floors of these pits (Samford 1988). In addition to being used as storage places for food and household items, there is documentation that root cellars were also used as hiding places for stolen goods. Ex-slave Charles Grandy explained in an early 20th-century interview that he and other slaves hid stolen chickens in a trap door cut through the floor of the house. At the Kingsmill plantation excavations, one root cellar was found to contain several entire wine bottles bearing the seal of master Carter Burwell (Kelso 1984). After ceasing to serve as storage areas for vegetables and household items, root cellars apparently became a dumping place for kitchen and other garbage, since animal bones, broken glass, ceramics and other debris are contained within the soil filling the holes.

Numbers of root cellars found within buildings vary. As many as 18 root cellars were located within the foundation wars of one slave house at Kingsmill (Kelso 1984). Although these cellars were generally just holes cut into the clay and covered with boards, brick and wood lined examples were not uncommon, such as a brick-lined cellar found recently in the early 18th-century kitchen on the Grissell Hay property in Williamsburg (Samford 1990).

The three root cellars located at Yorkshire were probably confined within one structure. Although the size of the building is impossible to determine from the information 17 recovered, it would have had to measure at least 30' NS × 14' EW in order to contain all three root cellars. This fits with evidence from the Desandrouins Map, which shows a structure standing in this general location along the ravine in the late 18th century. Although a Ludwell plantation house stood at Rich Neck in the 17th century, it may have disappeared by the time the Desandrouins Map was drawn. Testing done in 1988 suggested a 17th-century main house south of the terminus of the road shown on the map (Samford and Brown 1988). No such structure appears in this late 18th-century depiction of the property, while what appear to be support structures are shown clustered on either side of this road. These may have been, the buildings used to house Philip Ludwell's twenty-one slaves, livestock, 1600 lb of tobacco and agricultural implements listed at the Rich Neck plantation site in the 1767 inventory.

Artifacts from Root Cellars

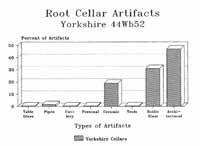

The artifacts from the root cellars provide clues as to what life was like for the building's inhabitants. The artifacts were largely of a household nature, and included items used daily by the structure's occupants, including ceramics, wine bottles, and tobacco pipes. The quantity of material recovered from the root cellars was small, numbering only 630 items (303 from Cellar A and 327 from Cellar B). A large percentage of the artifacts showed signs of burning. This, plus the charred wood and ash found in Root Cellars A and B, suggest that the building standing over these cellars was destroyed by fire. Figure 9 shows the artifacts broken down into categories.

Ceramics and glass represent some of the most numerous of he artifacts recovered. Ceramics are one of archaeologists' most datable artifact categories, and the root cellar ceramics date largely to the last thirty years of the 18th century. Most prevalent were creamware and pearlware tablewares, which began manufacture in England during the third and fourth quarters of the 18th century (Noël Hume 1978:125, 128). The latest ceramic fragment found within a root cell was a burned sherd of a pearlware shell-edged plate, with an embossed rim whose production dates between around 1815 and 1830 (Miller, personal communication). Its inclusion in the cellars therefore, date the destruction of this building after 1815. The ceramics will be discussed in greater detail later.

Tools speak to the variety of work activities that were taking place at the site; several fragments of barrel hoop suggest barrels for storing supplies or other items (probably tobacco in this case), and a wood chisel may have been used in making these barrels or in other woodworking activities. One horseshoe found in Root Cellar A suggests the presence of horses or similar draft animals. Since tobacco was being produced at Rich Neck in the second half of the 18th century, as is evident from documentary sources, a horse would have been needed for plowing and hauling. Two pieces of casting waste, one lead and the other copper alloy, suggest that some metalworking may have been done on the property.

Animal bone, left over from butchering animals for food, are common artifacts on 18th-century domestic archaeological sites. At the Yorkshire site, however, only nine bone fragments were recovered from the root cellars. This was due largely to damage sustained by the bone from the fire which is believed to have destroyed the structure. All of the bone

18

Figure 9. Root cellar artifacts, Yorkshire 44Wb52.

were badly burned, and with one exception, unidentifiable except as medium-sized mammal (Gaynor, personal communication)., The one identifiable bone fragment was a tooth from an immature sheep or goat. The only other food remain discovered as a burned fragment of walnut shell. This scanty faunal and botanical information unfortunately makes assessing the diet of the building's inhabitants impossible.

Figure 9. Root cellar artifacts, Yorkshire 44Wb52.

were badly burned, and with one exception, unidentifiable except as medium-sized mammal (Gaynor, personal communication)., The one identifiable bone fragment was a tooth from an immature sheep or goat. The only other food remain discovered as a burned fragment of walnut shell. This scanty faunal and botanical information unfortunately makes assessing the diet of the building's inhabitants impossible.

As mentioned previously, the inhabitants at the site ate from ceramic tablewares (Tables 1 and 2), some of them very fancy by the standards of the day. Although this would seem incongruous for a slave house site, archaeologists have been finding some so-called "luxury" items in slave assemblages. To explain this, perhaps it is worth examining the means through which slaves acquired material possessions. Usually, slave owners provided a basic "kit" for slaves; this kit included clothing, an iron cooking pot, bedding materials, and some basic food items. Slaves supplemented this basic kit in several ways: by hunting, fishing, planting gardens and raising chickens, slaves were able to add variety and nutrition to their diet. Slaves could also participate in the market economy to some extent through bartering items or services in non-monetary exchanges. Small amounts of money could be obtained through selling eggs, vegetables, or hand-crafted items, and money was sometimes given to slaves as gratuities. Research has shown that some Virginia store owners record slaves purchasing items, usually alcohol, sweeteners, or clothing-related goods (Martin 1991). "Hand-me-downs" from slave owners may have been another way in which slaves obtained material goods; on several occasions, Joseph Ball sent his old clothes from England to his Rappahannock River plantation with specific instructions as to the slave recipients of these items (Ball Letterbook).

19| Type | Quantity |

| Creamware Royal rim plate | 1 |

| Creamware Royal rim soup plate | 1 |

| Creamware tankard | 1 |

| Creamware overglaze printed tankard | 1 |

| Creamware bowl | 1 |

| Creamware saucer | 1 |

| Pearlware shell edge plate | 1 |

| Pearlware dish/platter | 1 |

| Pearlware handpainted saucer | 1 |

| Chinese porcelain overglaze cup | 1 |

| Black glazed redware hollow vessel | 1 |

| Lead glazed earthenware, Frechen | 1 |

| English brown stoneware, unidentified | 2 |

| Leaded glass wine stem | 1 |

| TOTAL | 15 |

| Type | Quantity |

| Delftware drug jar | 1 |

| Creamware gravy | 1 |

| Wine bottles | 4 |

| TOTAL | 6 |

As can be seen, there were a variety of ways that African-American slaves could obtain goods. In their free time, slaves probably focused their major efforts on ways to make life measurably better, such as procuring more or better food, or improving their clothing or housing. It is not unreasonable, however, to think that some African-American slaves would have been interested in items designed, not to improve the quality of their lives but to enhance their status or individuality. For example, Ann Martin's (1991) research on Virginia merchants has found that the slave women who were buying items in stores were purchasing hats, mirrors, and ribbons. Although hats could serve solely the functional purpose of protection from the sun or other natural elements, the ribbons and mirrors can be seen as vanity purchases. Since slave clothing was usually issued by the plantation owner, and would have been similar in cut and fabric, ribbons and hats would have been a way to individualize clothing, an assertion of a slave's perrsonal style. The same could hold true for household item as well. Take, for example, a Polish visitor's description of a late 18th-century slave house at Mount Vernon:

We entered one of the cabins of the Blacks, for one can not call them by the name of houses. They are more miserable than the most miserable of the cottages of our peasants. The 20 husband and wife sleep on a mean pallet, the children on the ground; a very bad fireplace, some utensils for cooking, but in the middle of this poverty some cups and a teapot (Niemcewicz 1965).

Although lacking even the basic necessities for comfort, this African-American family had managed to obtain a teapot and cups, symbols in the 18th century of gentility and the social ceremony of drinking tea. The slave owners of these ceramics may have never used these items for the consumption of tea—they could have been merely decorative, or the cups could have been used for holding any liquids or the teapot could have been a container for flowers. Despite the uses these objects may have served other than tea-related, the status of such items may have still been attached to owning them.

Ceramics of English and European manufacture are common on Chesapeake slave sites, indicating that slaves, not surprisingly, were using the same types of ceramics which were available to Anglo-American colonists. Generally, however, these were common tableware vessels (plates, bowls, drinking vessels) in relatively underdecorated or inexpensively decorated forms. For example, the creamware bowls and white salt glazed stoneware plates recovered from the Carter's Grove slave quarter excavation were not decorated by any painting or elaborate molding (Samford 1988). Some of the Yorkshire ceramics appears to be atypical, however, including expensive wares in specialized vessel forms, such as a transfer printed tankard, Chinese overglaze porcelain, and a creamware gravy boat. The majority of the ceramics dated from the last quarter of the 18th century, while one fragment provides a later date (post 1815) for the building's destruction. Thus, what may be evident here is that older ceramics were being used by the quarter inhabitants, types which were no longer fashionable among the wealthier classes. It is impossible to determine how the Rich Neck slaves acquired these ceramics, although they may have been hand-me-downs from the master, or even purchased by the slaves themselves.

Although 47% of the artifacts recovered from the two root cellars wore architectural in nature, these included no fragments of window glass. Whereas glass-paned windows had become more common in 18th-century Virginia houses, they were by no means universal, particularly among the lower social and economic ranks. Given this absence of window glass, the windows in this structure would most likely have been protected with wooden shutters. The vast majority of the architectural artifacts were hand-wrought iron nails. The discrepancy in proportions of architectural artifacts between the two cellars (26% of the total artifact assemblage in Cellar A and 68 % in Cellar B) can be easily accounted for by the different techniques used in constructing the two pits. A lining of wood, held together with nails, was evident in Root Claar B, accounting for its greater concentration of nails. This wooden lining would have given the root cellar more structural stability than one merely excavated into the subsoil clay by preventing erosion of the cellar walls from rain and ground water.

In addition to the differences in numbers of architectural artifacts, there were other discrepancies between the two cellars which are not so easily explained (Figure 10). Root Cellar A contained almost ten times as much bottle glass as Root Cellar B, while B contained over twice as many ceramic fragments. This may suggest a difference in function for the cellars, but much more comparative work in the Chesapeake needs to be completed

21

Figure 10. Root cellar artifacts, Root Cellars A & B.

before this type of question can be addressed. There were very few personal items, tools, or status items like cutlery and leaded table glass (stemmed wine glasses, decanters, or tumblers) discarded into the cellars.

Figure 10. Root cellar artifacts, Root Cellars A & B.

before this type of question can be addressed. There were very few personal items, tools, or status items like cutlery and leaded table glass (stemmed wine glasses, decanters, or tumblers) discarded into the cellars.

Comparative Analysis

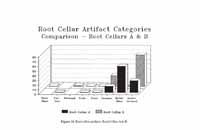

Artifacts from the Yorkshire site have been compared with those from a site with similar characteristics and dating. The archaeological findings from the Carter's Grove slave quarters, excavated in 1971 by William Kelso, were very similar in appearance to the Yorkshire site. A total of thirteen late 18th-century root cellars, probably from three buildings, was discovered. The site of these structures had also been plowed, so the only tangible structural remains represented there were the root cellars. For the purposes of this discussion, the root cellar artifacts from both the Carter's Grove and the Yorkshire site were each treated as one group or assemblage; comparing this material show that there were some differences in the two groups of artifacts (Figure 11).

The most striking differences were in the quantities of bottle glass and tobacco pipes. While this may simply indicate personal preference, this tends to suggest that the Yorkshire slaves had greater access to alcohol and relied less on the use of tobacco. Personal items were present in small numbers in both assemblages. While the Carter's Grove assemblage contained clothing accessories, several clay marbles, a Jew's harp, and mirror glass, the only personal items in the cellars at Yorkshire were a copper alloy button and buckle.

22 Figure 11. Root cellar artifacts, comparison of Yorkshire & Carter's Grove.

Figure 11. Root cellar artifacts, comparison of Yorkshire & Carter's Grove.

Nails made up the largest part of the architectural debris from both groups. The high percentage of architectural material to other categories of artifacts may be related to the sparseness of all other artifact categories from the slave assemblages. Two root cellars at Carter's Grove and one from Yorkshire were also lined with wooden boxes, contributing to the high number of nails present among the artifacts.

Ceramics comprise one of the larger categories of items recovered from the root cellars. A comparison of Yorkshire and Carter's Grove shows largely similarities. Over half of the ceramics (based on sherd counts) from each site were refined earthen and stonewares in tableware forms such as plates and bowls. Colonoware, a low-fired hand-built pottery attributed to Native Americans or African-Americans, was not found in significant quantities at either site. Chinese porcelain was present in small quantities in the ceramic assemblage of both sites (at Carter's Grove, porcelain made up 5% of the ceramics and only 1% at Yorkshire). Although Chinese porcelain was the most expensive ceramic available in the 18th century, it has been found in small amounts on many Chesapeake slave sites.

In total, the two groups of artifacts are similar in most respects. Overall numbers of artifacts were small from both sites, indicating that the material life of a late 18th-/early 19th-century slave was far from sumptuous. Of the artifacts, the greatest proportions were architectural and food related items. Wooden structures, such as these appeared to 23 have been, required nails in their construction, thus the disproportionate numbers of nails. The lack of window glass and other architectural items such as padlocks suggest a rudimentary, "no-frills" housing for these occupants. Categories of items relating to food storage, preparation and consumption were also high, while personal items were low, perhaps indicating the inhabitant's primary effort were spent on dealing with the necessities of life.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Documentary and archaeological evidence suggest that the archaeological remains found on the Yorkshire Drive property were once part of a slave quarter on the Rich Neck Plantation. The artifacts compare favorably with those excavated from the slave quarters at Carter's Grove, dating, like this site, to the late 18th and early 19th centuries. More comparative studies of slave-related assemblages needs to be completed to show the range of conditions for slaves in the 18th and 19th centuries. These studies could be used to address questions about the quality of African-American life in the 18th century, strategies of slave survival and self-sufficiency and how African slaves adapted to the new environment and the constraints of bondage.

Although some outlying plantations have been excavated in the Williamsburg area, most notably those at Kingsmill, the Rich Neck plantation could prove very significant in light of supporting documents. Late 18th-century plantation records, of the Ludwell family, used in conjunction with archaeological research on the Rich Neck Plantation, could provide important information on provisioning in the colonial period. The Rich Neck site has very high potential for research. Areas with a high potential for containing valuable archaeological information include the ridge tested in 1988 and suspected to be the site of the Rich Neck plantation house (see Samford and Brown 1988). Other areas which have not been tested archaeologically but appear from a walkover survey to be potentially sensitive are the wooded area east of Walsingham Academy, and the ridge bounding College Creek to the south of Holly Hills.

It is the recommendation of this report that the remainder of the site, especially the portion believed to contain the plantation house, be preserved in plaice. If development, or further damage through logging is slated for this property, further archaeological examination of the site should be a high priority.

Bibliography

- 1911

- Ludwell Family. William and Mary Quarterly 19(3), 1st series.

- Ball, Joseph Joseph Ball Letterbook. Documents on file at Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, Williamsburg, Virginia.

- 1987

- Phase II Evaluation Study of the Archaeological Resources Within the Proposed Route 199 Evaluation Corridor Alternate, A Revised and A-2. Report submitted to the Virginia Department of Transportation by the Office of Archaeological Excavation, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1981

- Impermanent Architecture in the Southern American Colonies. Winterthur Portfolio 16: 135-196.

- 1954

- Green Spring Plantation in the 17th Century. Unpublished report on file at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library.

- 1781

- Plan du terrein a'la Rive Gauche de la Riviere de James vis' a vis Jamestown en Virginia. Copy on file at Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library.

- 1990

- Personal communication.

- 1971

- Letter to Dorothy B.J. Ross, date 2-23-71. In Letter File, Research Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1984

- Kingsmill Plantations 1619-1800: Archaeology of Country Life in Colonial Virginia. New York: Academic Press.

- 1986

- Mulberry Row: Slave Life at Thomas Jefferson's Monticello. Archaeology : 28-35.

- 1987

- The View from the Midden:An Analysis of Midden Distributions and Composition at the van Sweringen Site, St. Mary's City, Maryland. Historical Archaeology 21(2):3 -59.

- 1913

- Appraisement of the Estate of Philip Ludwell, Esqr. Decd. (From the Ludwell Papers, Virginia Historical Society). Virginia Historical Magazine 21:395-416. 26

- 1991

- Buying Your Way to the Top: Acquisition Patterns of Consumer Goods in Colonial Virginia. Paper presented at the Society for Historical Archaeology Conference, Richmond, Virginia.

- 1976

- Letter to Carolyn L. Mears, dated 2-18-76. In Letter File, Research Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1987

- Adventurers of Purse and Person, Virginia, 1607-1624. Richmond: The Dietz Press, Inc.

- 1990

- Personal communication.

- 1965

- Under Their Vine and Fig Tree; Travels through American in 1797-1799, 1805 with Some Further Account of Life in New Jersey. Translated and edited by Metchie Budka. Elizabeth, New Jersey: The Grassmann Publishing Company, Inc.

- 1978

- A Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America. New York: Alfred Knopf.

- 1979

- Cavaliers and Pioneers: Abstracts of Virginia Land Patents and Grants 1623-1666. Volume I. Reprinted in 1979 by Virginia Book Company, Berryville, Virginia.

- 1781

- 39e Camp a Williamsburg le 26 Septembre… [Amerique Campagne, 1781]. Plan des differents campes occupes par l'Armee aux orderes de Mr. Le Comte De Rochambeau. Copy on file at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library.

- 1988

- Memo to Cary Carson concerning the Carter's Grove Slave Quarters. On file at the Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia.

- 1990

- "Near the Governor's": Patterns of Development of Three Properties Along Williamsburg's Palace and Nicholson Streets in the 18th Century. Master's thesis, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia.

- 1988

- Archaeological Survey of the Rich Neck Plantation. Report prepared for the Tidewater Cultural Resource Center, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia. 27

- 1935

- Memo to Mr. Goodwin re Green Spring. Date 11-18-35. In Greenspring file, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library.

- n.d.

- Southall Papers. Folder 297. Letters of William Lee. Virginia Historical Society.

- 1751

- May 24 1751 edition. William Hunter, editor.

- 1771

- October 10, 1771 edition. Purdie and Dixon, editors.

Appendix 1.

Artifact Inventory

Note: Inventory is printed from the Re:discovery cataloguing program used by Colonial Williamsburg, manufactured and sold by Re:discovery Software, Charlottesville, Virginia.

Brief explanation of terms:

- Context No. Arbitrary designation for a particular deposit (layer or feature), consisting of a four-digit "site/area" designation and a five-digit context designation.

- TPQ "Date after which" the layer or feature was deposited, based on the artifact with the latest initial manufacture date. Deposits without a diagnostic artifact have the designation "NDA," or no date available. Listing The individual artifact listing includes the catalog "line designation," followed by the number of fragments or pieces, followed by the description.

| AA | 1 | Porcelain, sherd, Ch porcelain, painted under, blue, base, probably part of a tea bowl |

| AB | 1 | Ceramic, tobacco pipe, imported, bowl |

| AC | 1 | Bone, faunal bone |

| AD | 1 | Glass, sherd, wine bottle, burned |

| AE | 2 | Glass, sherd, wine bottle |

| AF | 2 | Iron, nail, fragment |

| AG | 4 | Plasters plaster, lime plaster |

| AA | 8 | Glass, sherd, wine bottle |

| AB | 8 | Glass, sherd, wine bottle, burned |

| AC | 1 | Ceramic, tobacco pipe, imported, bowl |

| AD | 2 | Ceramic, tobacco pipe, imported, stem |

| AE | 3 | Glass, table glass, molded design, polychrome, laminated, cased |

| AF | 3 | Refined earthenware, sherd, pearlware, undecorated |

| AG | 2 | Refined earthenware, sherd, pearlware, painted under, polychrome |

| AH | 25 | Refined earthenware, sherd, creamware, undecorated |

| AI | 1 | Refined earthenware, sherd, creamware, painted over, polychrome |

| AJ | 2 | Refined earthenware, sherd, creamware undecorated, burned |

| AK | 2 | Shell, shell |

| AL | 1 | Other organic, organic subst, burned, marl-like concretn, brick, shell, charcoal |

| AM | 7 | Stoneware, sherd, fulham sw, three possibly burned |

| AN | 3 | Porcelain, sherd, Ch porcelain, undecorated |

| AO | 1 | Porcelan, sherd, Ch porcelain, painted over, color missing |

| AP | 1 | Porcelain, sherd, Ch porcelain, painted over, polychrome |

| AQ | 1 | Porcelain, sherd, Ch porcelain, painted under, blue |

| AR | 1 | Copper alloy, spigot, fragment |

| AS | 2 | Glass, stemmed glass, clrless lead, knopped stem |

| AT | 3 | Glass, container, clrless non-ld |

| AU | 1 | Glass, container, clrless non-ld, Owen's scar |

| AV | 1 | Refined earthenware, sherd, refined ew, burned |

| AW | 1 | Ceramics sherd, other porc, burned, possibly soft paste |

| AX | 1 | Stoneware, sherd, Westerwald |

| AY | 6 | Refined earthenware, sherd, whiteware, undecorated |

| AZ | 1 | Iron, pot non-ceramic, cast |

| BA | 1 | Glass, jewelry, colored, other molded decoration, other color, complete, amber, intaglio, classical profile |

| BB | 2 | Bone, faunal bone |

| BC | 3 | Bone, faunal bone, burned |

| BD | 2 | Other metal, casting waste, possibly copper alloy? |

| BE | 5 | Glass, container, colored, four lime green, one opaque white |

| BF | 2 | Glass, container, mang solarized, other molded decoration, pieces mend—molded at top of one piece |

| BG | 1 | Glass, container, colored, aqua, lettering/numbers |

| BH | 1 | Stone, architect slate |

| BI | 1 | Stone, stone, cobble? |

| BJ | 1 | Iron, pipe, rolled/sheet |

| BK | 4 | Stone, stone, quartzite |

| BL | 1 | Stone, stone, worked |

| BM | 1 | Ceramic, sherd, other ew, damaged |

| 30 | ||

| BN | 1 | Ceramic!, tile, paving tile, * glazed bathroom the |

| BO | 1 | Iron, nail, less than 2 in, wrought |

| BP | 1 | Iron, nail, two to four in, cut |

| BQ | 15 | Iron, nail, fragment |

| BR | 1 | Iron, nail, wrought, with washer at head, possible rivet |

| BS | 29 | Plaster, plaster, lime plaster |

| BT | 2 | Cement, Portland cement |

| BU | 1 | Other organic, organic subst, wax-like substance |

| AA | 2 | Stoneware, sherd, fulham sw, burned |

| AB | 17 | Stoneware, sherd, fulham sw, damaged |

| AC | 12 | Refined earthenware, sherd, refined ew, burned |

| AD | 10 | Earthenware, sherd, delftware Eng, burned |

| AE | 1 | Refined earthenware, sherd, creamware;, undecorated, rim |

| AF | 2 | Ceramic, tobacco pipe, imported, other molded decoratlaon, burned, possibly German or English |

| AG | 1 | Stoneware, sherd, staffs brown |

| AH | 1 | Pewter, unid hardware, burned |

| AI | 1 | Coal, coal |

| AJ | 1 | Brick, bricketage, burned |

| AK | 2 | Glass, Container, colored, very thin- possibly French wine bottle |

| AL | 91 | Glass, shard, wine bottle, burned |

| AM | 77 | Glass, sherd, wine bottle |

| AN | 1 | Glass, sherd, wine bottle, hand tooled finish |

| AO | 1 | Iron, horseshoe, complete |

| AP | 1 | Iron, barrel hoop |

| AQ | 1 | Iron, knife, table, blade |

| AR | 1 | Steel, unid hardware, possible wood chisel point, beveled edge |

| AS | 1 | Iron, spike, wrought |

| AT | 57 | Iron, nail, fragment |

| AU | 3 | Iron, nail, less than 2 in, wrought |

| AV | 16 | Iron, nail, two to four in, wrought |

| AW | 1 | Iron, nail, over four in, wrought |

| AX | 1 | Iron, spike, forged, * narrow-gauge r ilroad tie |

| AY | 1 | Iron, unid hardware, wrought |

| AA | 2 | Ceramico tobacco pipe, imported, stem | |

| AB | 1 | Ceramics tobacco pipe, imported, bowl | |

| AC | 1 | Ceramic tobacco pipe, imported, other molded decorat on, bowl | |

| AD | 3 | Shell, shell | |

| AE | 9 | Bone, faunal bone, eight calcified | |

| AF | 19 | Charcoal, charcoal, possibly just parts of a burned root | |

| AG | 1 | Stone, tone, possibly worked | |

| AH | 1 | Stone, lake, quartzite | |

| AI | 2 | Stone, ebitage, quartzite | |

| AJ | 1 | Stone, reform, quartzite, probably i tented as a point | |

| AK | 10 | Glass, herd, wine bottle, one damaged possibly burned | |

| AL | 2 | Glass, Oherd, wine bottle, burned | |

| AM | 1 | Glass, stemmed glass, cirless lead, k,opped stem, burned | |

| AN | 1 | Glass, container, clrless non-ld, | |

| AO | 1 | Glass, container, colored | |

| 31 | |||

| AP | 2 | Copper alloy, button, one piece, compete, small clothing, loop shank | |

| AQ | 3 | Copper lloy, buckle, fragment | |

| AR | 1 | Copper ~lloy, casting waste | |

| AS | 1 | Lead, casting waste, unusual form | |

| AT | 1 | Ceramics tile, roofing the | |

| AU | 3 | Refined earthenware, sherd, pearlware undecorated | |

| AV | 2 | Refined earthenware, sherd, pearlware painted under, blue | |

| AW | 1 | Refined, earthenware, sherd, pearlware | shell edge, blue, burned |

| AX | 1 | Refined'!earthenware, sherd, pearlware, undecorated, burned | |

| AY | 25 | Refined earthenware, sherd, creamware undecorated | |

| AZ | 1 | Refined earthenware, sherd, creamware printed over/ba~, black, base, sea/ocean moti 7 | |

| BA | 5 | Refined earthenware, sherd, creamware undecorated, damaged, possibly burned | |

| BB | 9 | Refined earthenware, sherd, creamware undecorated, burned | |

| BC | 1 | Porcelain, sherd, Ch porcelain, painted over, color missing | |

| BD | 2 | Coarse earthenware, sherd, bk-gl redw re | |

| BE | 2 | Coarse earthenware, sherd, coarseware' lead glaze, rim, possibly French | |

| BF | 5 | Coarse arthenware, sherd, coarseware' lead glaze, gamaged, possibly French, poss bly burned | |

| BG | 10 | Stoneware, sherd, English sw | |

| BH | 1 | Other organic, seed, burned, walnut shell | |

| BI | 2 | Iron, unid hardware, one possible barrel hoop | |

| BJ | 158 | Iron, nail, fragment | |

| BK | 35 | Iron, nail, two to four in, wrought | |

| BL | 1 | Iron, hook non-clothg, possible fireplace hook | |

| AA | 1 | Ceramic, tobacco pipe, imported, stem |

| AB | 1 | Bone, faunal bone |

| AC | 1 | Refined earthenware, sherd, refined e w, damagedo finished surfaces missing |

| AD | 3 | Refined earthenware, sherd, creamware undecorated |

| AE | 2 | Refined earthenware, sherd, pearlware, painted under, blue |

| AF | 1 | Refined earthenware, sherd, pearlware, painted under, brown, rim, small hollowware cup? |

| AG | 1 | Glass, container, clrless non-ld, |

| Ceramic | Type | Form | Context |

| Delftware | burned | drug jar | 0002 |

| Creamware | Royal rim | plate | 0001 |

| Creamware | painted overglaze, green | sherd | 0001 |

| Creamware | Queen's rim, burned | gravy | 0002 |

| Creamware | Royal rim | plate | 0006 |

| Creamware | Royal rim | soup plate | 0006 |

| Creamware | burned | tankard | 0006 |

| Creamware | bowl | 0006 | |

| Creamware | saucer | 0006 | |

| Creamware | printed overglaze, black | tankard | 0006 |

| Pearlware | painted underglaze, blue | saucer | 0001 |

| Pearlware | painted underglaze, brown | cup | 0001 |

| Pearlware | shell edge, blue, burned | plate | 0006 |

| Pearlware | dish | 0006 | |

| Pearlware | painted underglaze, blue | saucer | 0006 |

| Pearlware | painted underglaze, blue | bowl? | 0007 |

| Pearlware | painted underglaze, blue | bowl? | 0007 |

| Pearlware | painted underglaze, brown | mug? | 0007 |

| Chinese porcelain Canton | painted underglaze, blue | covered dish | 0001 |

| Chinese porcelain | sauce tureen lid | 0001 | |

| Chinese porcelain | painted overglaze, red, burned | saucer | 0001 |

| Chinese porcelain | painted underglaze | tea bowl | 0000 |

| Chinese porcelain | painted overglaze | cup | 0006 |

| Black glazed redware | hollow vessel | shered | 0006 |

| Lead glazed earthenware | possibly French | dish | 0006 |

| Westerwald | sherd | 0001 | |

| English brown stoneware | burned | sherd | 0006 |

| English brown stoneware | sherd | 0006 | |

| Leaded glass | burned, stem | wine glass | 0006 |

| Wine bottle glass | rim | 0002 | |

| Wine bottle glass | neck rim | 0002 | |

| Wine bottle glass | neck rim | 0002 | |

| Wine bottle glass | neck rim | 0002 |